- forum+, Krieg in der Ukraine, Kultur

Art in Ukraine, Part II:

Art as a Weapon

As most Ukrainians, artists too are affected by the Russian aggression. Yet artists have their own way of articulating their experience of wartime. For some, war is just part of life, for others art is a weapon that helps fight the aggressor and others still think that the experience of war simply cannot be expressed. In the following two-part article, a younger generation of Ukrainian artists, most of them based in Kyiv, talk about their experience of the war, their specific artistic form of expression and their view on art in general.

War Diary

Zhenya’s experience of the war is intense. Shortly, before the invasion she, her brother and her boyfriend decided to leave Kyiv and meet her brother’s godfather and his family in Makariv Raion, a district West of Kyiv. The idea was to be in a bigger, safer group of trusted people.

But the idea turned out to be very dangerous. Everybody expected the Russians to attack Kyiv from the East, and not from the North-West, that is from Belarus. At that time, and unknown to Zhenya and her companions, Makariv and its surroundings Bucha and Irpin, were to become one of the most heated and cruel places of the war in Ukraine, including rape and mass executions of Ukrainian civilians. Zhenya could have been one of them.

Usually an hour’s drive from Kyiv, it took Zhenya and her companions ten hours to get there, because so many people were fleeing the capital. Shortly after they arrived, they were stuck, because during the first days, fighting between Russian and Ukrainian forces was so intense that it was impossible to leave the house. “I had this silent inability to act, powerlessness, and this was terrible, because nobody knew what will happen next.”

After the second day electricity was cut, meaning that there was no heating, no internet, no functioning water pump. Because of short food supply they had to ration. “A luxurious dish for dinner was rice with corn and salmon instead of simple buckwheat.” They were cut off from the rest of the world, “they” meaning eight people: Zhenya, her younger brother, her boyfriend, the godfather of her brother named Yura, the godfather’s wife, two small children, aged five and seven, and the grandmother. The house was too small for the size of the group, so everybody was basically just staying put. With the Russians hiding in the trenches in the forest behind the house, it was impossible to leave the house. Yura, the godfather, was the only one exploring and investigating the situation in the village and trying to get water from the well. At one point, he ran into Russian tanks and soldiers. They started firing and chasing him, so that he had to flee. For almost three weeks the whole group was locked up in the tiny house, until the Russians got pushed back by the Ukrainian forces.

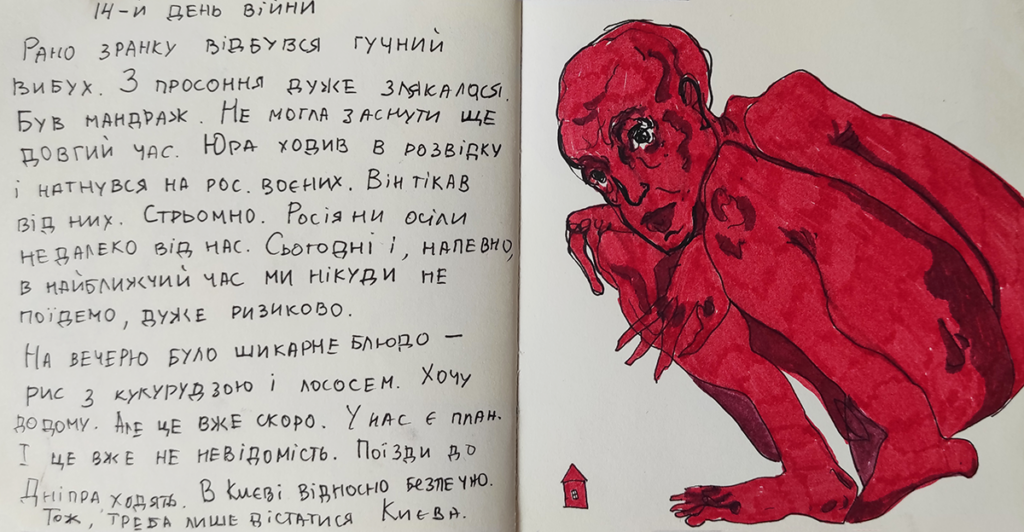

The war diary that Zhenya started came rather unexpectedly. “I was in this house and nothing was happening, and it’s this very weird state, because you cannot do anything, you have zero plans for the future, zero ideas, you’re in limbo.” Zhenya was supposed to submit her bachelor thesis, and while still having connection, she was exchanging messages with her thesis advisor, who encouraged her to do something in order to avoid depression and apathy. “I was telling myself, yes, I’m an artist, I should do something. I can’t just sit here and do nothing, and get depressed.” So after the fifth day she started her diary. All that Zhenya had was a red marker, a pen and a notebook.

Zhenya’s goal was on the one hand to grasp the situation, because she did not know what was happening to her, and on the other hand to keep a record. But very soon she also started to draw. Yet this turned out to be more difficult as initially thought, because she had no clear image of what to draw, and then there was a simple physiological issue: her hands were shaking because the situation was so stressful. “That is why the images came out shaky, uncertain, lost, and confused.” Explosions wrenched her from sleep so that half-awake, scared and confused she tried to put something down on paper. The only way out was to draw.

The figure that reappears in her diary is a self-portrait. “The house is something that I wanted so dearly. It is the symbol of home and my biggest fear was that something would happen with my family, and I had no doubt that similar things were happening in Kharkiv, Kherson, and all the places that were dear to me.” Similarly, her parents were worried about her well-being.

In another picture, Zhenya drew the two children and their mother. “They look very scary, because everything looked very scary at that time.” Zhenya remembers that it was very difficult to reason with children, because they asked the most difficult questions. “You’re sitting there and they ask you directly: are we all going to get killed? I did not know what to say.”

Depending on the situation, Zhenya sometimes used text, sometimes she simply drew, and sometimes she combined both. In another drawing, she writes the phrase: ‘you have to open your mouth’. Yura told everybody that if there is a very loud explosion, they should cover their ears and open their mouth in order to prevent their eardrums from bursting.

Their house was situated in no-man’s land, so to speak, between the Russian and the Ukrainian forces firing at each other. At some point the shooting became very intense and an explosion by a bomb destroyed the roof of a neighbouring house only twenty meters away. “At that point you understand that the only hope you have is that you don’t get hit, and if you get hit then you’re done.” The neighbours hid in the basement and survived.

Leaving town was almost as dangerous as staying inside. Evacuation corridors were organised for civilians to flee Russian occupied territory. It was crucial to leave in groups, because single cars on the streets were bombed by the Russians, no matter if they waved white flags, or had signs saying “children inside”. For forty-five hours, seventy to eighty cars had to wait at a checkpoint before being able to continue driving westward. Zhenya and the other eight people from the house were all packed in one sedan. “There was no way to get out of the car to stretch or to go to the bathroom, because the Russians would shoot along the cars.”

Once they passed the tanks and soldiers, Zhenya arrived in Zhytomyr, but while the rest of the vehicle occupants continued to Lviv, she and her boyfriend turned East towards Dnipro, because that’s where her family was. “There was an old woman who started screaming: Are you out of your mind, why would you go to Dnipro now?” Zhenya simply started to cry hysterically. “All the tension and anxiety came out.” After they got to Dnipro, she didn’t need her diary as much.

For Zhenya, politics are everywhere. It is impossible to be apolitical. Art is certainly a weapon, but it is also important for artists to conceptualise and have an idea that is carried on in their works. In the end, the diary was about recording, letting go and then moving on. But what Zhenya realised the most is that “you can’t pause life. You can never go back to the way it was before, so this is the new reality you have to live with. It’s really important that Ukraine does not get forgotten.”

Collage Therapy

Annete is a doer: she’s an artist, has a certificate in art therapy, works as a curator and created her own art collective in Kyiv. Her passion is collage, but when she started in 2018 with collage, it had no solid representation in Ukraine. So she founded her own collective in 2021. “After a week I had a couple of hundred followers. The response was positive.” In July 2021 Annete organised a festival for contemporary collage in Ukraine. A month of exhibitions, workshops, lectures and movies. The participants couldn’t get enough, so Annete and some friends opened up a studio a month later. “The community of collage lovers is growing.”

The second collage festival was planned for August 2022, but with the Russian invasion in February plans changed drastically. Annete fled with her parents and her sister to Madrid, Spain. “We stayed with my friend’s family, and we had a very warm welcome. We became part of their family. We were really thankful to be able to stay with them.” Annete’s parents are still in Madrid, but after four months Annete decided to leave. She wanted to go home. Her partner was in Kyiv, her art projects were in Kyiv, in Ukraine she had connections to galleries and museums, and she felt like a foreigner in Spain. She felt lonely. “So in Summer when all the art projects start, I decided to come back.”

2021 was also the year when Annete started with art therapy. “I could feel the therapeutic effects on people. I had no background in psychology, I did not know how to properly do it. I was thinking about getting a certificate before the invasion, but I was too lazy, and then when the invasion happened, I felt that it was something that is going to be very much needed, also with kids.” In art therapy, anything can be used: drawing with your fingers, taking pictures, making collages, mixing art with music. “We talk, meditate, explain our creations, but mostly it’s about what comes from your heart and your soul.”

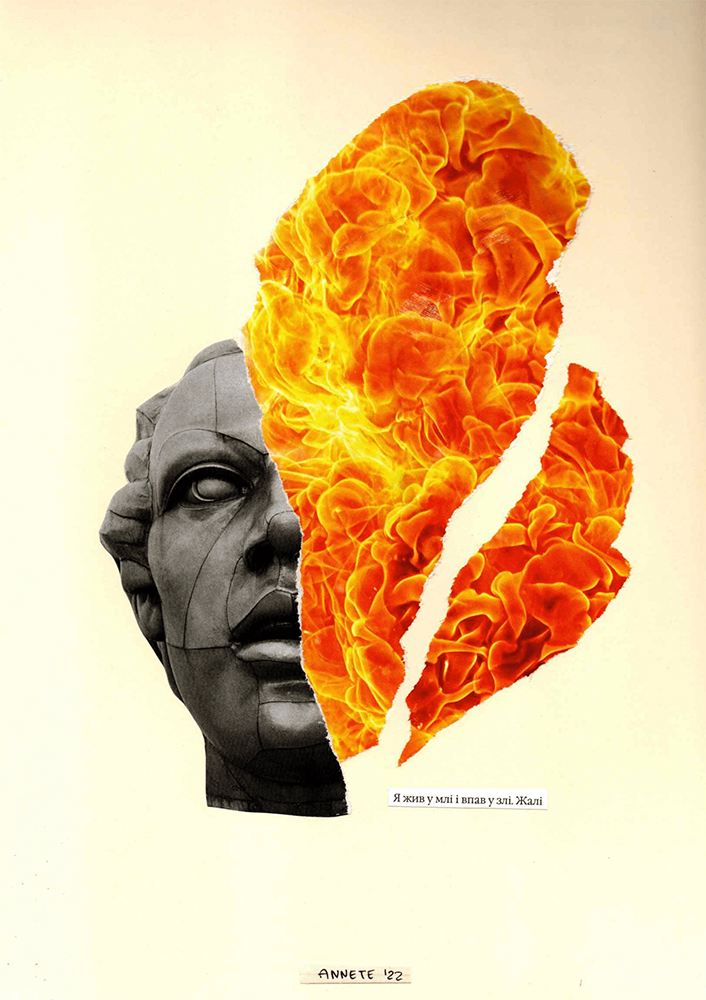

Annete discovered collage while she was living in Paris. “I was at a low point in my life, I was very depressed. I needed to find something for myself and so I started to collect magazines such as Vogue and I cut them. I was just playing with it.” What Annete loves about collage is that the narrative can be changed. The artist tears something out of an image, puts something else instead, and thereby creates a new world, a new dimension, of what they want to express. “I almost never have an idea, only when I glue something on the paper, and I look at it, I realize that it was there and that it needed to get out of me.” Collage became Annete’s therapy.

But, next to art therapy and her own practice, Annete also takes art to the streets. Together with a collage artist from Norway, “miss.printed”, Annete created the project “Stick together with Ukraine”. The idea is to curate public spaces all around Kyiv, with an online map showing the locations. “We collected triangle collages from more than twenty countries: Canada, Brazil, US, France, Singapore…” Annete was completely overwhelmed by the sheer number of collages that she received. “One of them said: ‘We see you’. It’s enough to realize that people are looking at your webpage, at the news, ask what is happening. We are seen, we are heard, and we are supported by this community. That’s important.”

Annete is also an activist. In online public talks, she tries to make her listeners aware of the suppressive Russian narrative. Annete highlights that Russia has killed Ukrainian artists, stolen art and tried to label Ukrainian art as their own throughout history. Russian narratives and products need to be cancelled now. “I was speaking Russian my whole life, but when the full-scale invasion happened I realised that I need to forget that language. I don’t want to speak it, I don’t want to communicate in it and so my family, my partner and my friends, we all switched consciously to Ukrainian. We were always thought of as Russians.” Annete wants to learn more about her own culture, her own language and discover Ukrainian history.

In the same sense, Annete criticises the Russian collage community. “They are not speaking against the Russian government, they left to Europe or to the States but they still support the regime, or they remain silent, which is the same thing.” The Russian collage community wanted to whitewash their reputation, but not revolt against their government. For Annete, art is about politics, art is a weapon. “Now it is our duty to show our culture and also show the crimes that the Russians are doing.” Art can help people to become more self-conscious and mature, not just Ukrainians, but the whole world. In this sense, art therapy is also activism. At first, it’s mostly about self-healing, but as people gain confidence, they can create something about activism and war, Annete concludes.

But as an activist, an artist also needs to be careful. Art should not become propaganda or ideology. “You can become a fanatic with slogans or propaganda for violence, but it’s not what we want to achieve. We want to be independent and live in peace.” For Annete, it’s important that her art is not invented propaganda, meaning that it should be real, it should represent what is happening and be the expression of the artist. “It’s coming out, whether it’s about the war or not.” There is always a loss, a collective pain. For Annete, art is about feeling what you create, what comes out of you.

Before the full-scale invasion Annete wasn’t really interested in politics or history. Even in 2014, when the war started, being sixteen years old, she had other things on her mind. But now it’s more important to her than ever. “If we are not going to learn our history, and learn from the mistakes in the past, it is going to happen again and again, because I don’t think that the Russians are going to stop.” It’s important for the present, but also the future, that is, “our children and the next generations. It is our duty to preserve our history.”

Annete studied international relations and cultural diplomacy in Kraków, Poland, but she never worked in that field. “Now, I think that I am actually using my studies as diplomat because we are connecting with everybody and did exhibitions all over Europe. My diplomatic purpose has been achieved.”

Portraits of Resistance

Nadia was born and raised in Kyiv. Before she became an artist, she worked as a photo model, but her work did not inspire her. She felt she was wasting her time and energy. She wasn’t contributing to the world or society.

Now that she’s a graphic artist she’s much more fulfilled, even though life has become more difficult. Nadia doesn’t work digitally, she draws lines meticulously and prefers black and white, but what she seems to love even more is Ukrainian history. For her, graphic design is a very powerful artform. “Graphic artists such as Vasyl Krychevsky were very important for Ukrainian culture. They designed money bills, emblems, logos, buildings.” Similar to Annete in regard to collage, Nadia sees it as her mission to popularise graphic art in Ukraine. “There are not many artists in analogue graphics. This movement is only developing. But it’s also more difficult.” You need to master the skill.

But Nadia has yet another mission. While graphic drawings are the form she chooses to express herself in, her art consists of portraits of persecuted and executed Ukrainian writers, poets, artists, singers, dissidents, journalists, Ukrainian nationalists who tried to promote Ukrainian identity, language, ideas and traditions. Whoever looks at Nadia’s portraits wanders with her through Ukrainian culture and becomes witness to Russian suppression of Ukrainian culture. There is for example Volodymyr Ivasyuk, songwriter and poet, whose body was found in a forest in 1979 close to Lviv hanging on a rope from a tree. It’s still not known if he committed suicide. There’s Alla Horska, a painter and dissident, who was killed under mysterious circumstances in 1970. There’s the infamous Vasyl Stus, poet, journalist and dissident, who spent thirteen years in detention, where he died in 1985. Then there are the members of the so-called “executed Renaissance”, a generation of Ukrainian writers, poets and artists who became victims to Stalin’s persecutions in the 1920’s and 1930’s: the writers Maik Yohansen and Valerian Pidmohylny were executed, the movie and theatre director Les Kurbas was murdered.

What these examples show is how the Russians killed the intelligentsia of Ukraine, over time, in different periods. “If we go back to Ukrainian history in the 1920’s or even earlier, Ukraine had the possibility to rebuild, but unfortunately, Ukraine lost, and the Soviet Union occupied Ukraine.” The executed Renaissance built on that loss and tried to maintain and develop a Ukrainian identity.

This responsibility towards the past is what, for Nadia, makes art a weapon, a war. “It’s an instrument to bring to the spectator some idea, some vision.” That responsibility towards the past continues until today: the artists of the 1930’s had a responsibility towards the beginning of the 1920’s, and the artists of the 1960’s had a responsibility towards the 1930’s. “And today, artists feel the same responsibility towards the past, the victims, the fight, the ideas. Art is not just about drawing something. It’s more.” The past is a source of creativity, for developing ideas. “The past creates conceptions for artists inside which we reflect and think, and then these thoughts become art. Artists need to have an idea, some term that they want do discuss with their viewer. Maybe it won’t be about the past, or the history, or the culture of your nation, it could be something else, but if you don’t have a concept, it’s empty art.”

Like Annete, Nadia does not believe that her art is manipulative propaganda or ideology. “I am talking about real history. For example, I could say: All the individuals in my portraits were killed by Moscow, therefore Moscow is bad. But, I can also say: they died at 28, and you will ask me: why?” For Nadia, it is absolutely central for Ukraine to create its own narrative of identity. For her, “Russia is the worst enemy that you can imagine. Abroad, they underestimate the informational and cultural power of Russia. During the last 300 years they used it against Ukraine. And now we have Ukrainians who believe the Russians, that we are for example a brother-hood nation, that we have the same culture. But it’s a myth, it’s not the truth.”

Nadia’s portraits are her contribution to the construction of a Ukrainian narrative opposing the Russian narrative. “I wanted to show that these people were truly victims, I wanted to emphasize their age, I wanted to depict them talented and beautiful, and create a contrast to the injustice. The beauty was destroyed by an aggressor, by repressions.” For Nadia, it is her technique, the detailed lines that bring the personalities closer to the viewer and maybe inspire the observer to read a book by Pidmohylny, for example.

In the end, the concept of renaissance does not only apply to the 1920’s. Nadia thinks that all these authors need to be rediscovered today. Then a real renaissance could happen. This is also the difference to Enlightenment. “Enlightenment is more when you know something about the person, when you only know the name, but not his biography, his influence. Yet, if you don’t even know the name, it’s more of a renaissance.” To have Enlightenment, first you need a renaissance. Today a new renaissance wave is emerging, but it is not as powerful as in the 1930’s, yet still very important to her.

Atlas of Peace

Radyslav is a versatile artist. He paints, draws and makes collages. His work ranges from abstract art to surrealistic coffee paintings. He also works as an interior design artist. The latter is how he makes money, how he survives.

Radyslav has made many artworks about the war, and they are all highly symbolic. One of his lithographic creations can be considered as mail art. The art piece is called simply “bird”, but it actually represents a lark, an important symbol for Ukraine. The buyer cannot only choose where he wants to send the donation, they can also choose how much they want to donate. “It’s difficult for people to donate, they have no trust where the money is going. So, you donate where you want and I will mail you this bird. I just need proof of donation.” Eighty-eight birds are black, for the remaining twelve red birds, donations go directly to Ukrainian snipers. The last, one hundredth letter, was auctioned. Radyslav doesn’t even know how much money he made. The symbolism of the piece is very important to him. “If you turn the bird around it becomes the trident.” The coat of arms of Ukraine. The flipped symbolism is central, because of the birds’ flight. “I wanted those one hundred birds to fly out of Ukraine, via Poland to the US.”

Another beautiful artwork by Radyslav is the representation of the Ukrainian letter ï as two flames burning in a candle. “The letter does not exist in many alphabets, and most definitely not in the Russian alphabet.” It stands for the Ukrainian language. The candle is not a mourning candle; it creates light by doubling it. It’s a strong light, a symbol of hope.

Before the war, Radyslav’s work was different. It was about his personal thoughts and experiences, but since the war started everything changed. “You have this responsibility, it is important to have this resistance, and to spread your idea, also around the world.” That’s why mail art is relevant. The art literally flies to its recipient. That’s what Radyslav likes about it, even if it’s only to Poland, 500 km away. Mail art creates a connection between people. “It’s not as easy as digital art. It’s an actual thing that I take personally to the post office.” It’s not an online buy, but a personal involvement. In this sense, Radyslav has the impression that he is bringing something to the people, that they’re receiving something from him. “I am not going out into the free world. People receive messages from a place that they cannot go to, because of the war zone.” For Radyslav it’s as if he’s in the middle of a burning fire, blazing away but not really caring. “You just get extinguished, and it’s the end. But the people who stand next to it, they want to have something, some memory. They are watching the news, and they don’t know what is really happening. They don’t experience it, they don’t know. But when you live in the process, it’s sort of a bubble, you don’t care.”

But symbolism can also backfire. When he was creating the symbol of the bird, he could have taken any symbol: the shape of Ukraine, the sunflower or the belltower of Saint Sophia cathedral, but all these symbols would have been too obvious, according to Radyslav. “If you create something, you have to do something that you do well, and it has to be meaningful and it has to have quality. Artistic quality.” Otherwise, it’s just a tacky souvenir.

For Radyslav, art is definitely a weapon. “In the same way that the writer is weaponizing the pen, the artist is weaponizing his tools, and as long as we don’t have the guns, these are the weapons we are using.” Radyslav believes that everybody has their own front, their own struggle, and art is a means to connect. “When you get a bird as a letter, you also get a sniper bullet. A real shell from the front.” Radyslav gets them from his friends. In a former life they were architects, now they are fighting at the front.

In Radyslav’s current unfinished project, he paints over pages in an old Soviet atlas, called “atlas myr”, where the Russian “myr” can mean both, world and peace. The wordplay is too good to be true. Radyslav covers every page with paint, so that the viewer can’t see the actual maps anymore. The boundaries between countries disappear. Every page will also feature different elements such as scratches representing scratches on the walls in prisons or bullet prints. “When you look at the maps like this, then it is all divided, different colours, different borders, but who created those borders, where are those borders coming from? Covering them up means that there is no difference in colours, the colours of the skin of people. It is all one big piece, it is all universal.” The piece obviously goes against the Russian narrative to regain old imperial territory. In the process of painting over pages, the book might also fall apart, be torn and worn, and that is exactly the idea behind it. “The book of peace, the catalogue of peace, cannot be clean and perfect, polished, with fresh paint on it, it has to go through this process of falling apart in order to achieve peace.” Art is similar to war; it’s a strenuous endeavour.

Art as a Shield

Art can indeed be a weapon, it can be used to harm, to propagate ideology and propaganda. Yet, in the current situation, by contributing to your own culture, Nadia believes Ukraine is rather using a form of defence than aggression. Art therefore becomes a shield for Ukrainians. “The Russians used culture as a weapon. But now, we Ukrainians have this shield, which protects us from this Russian world, this ruskiy myr.” A Russian world that Radyslav is trying to efface, with colours, using art as a weapon.

Read the first part here.

Olivier Del Fabbro ist ein luxemburgischer Philosoph und lehrt als Oberassistent an der ETH Zürich. Er forscht unter anderem zur Philosophie des Krieges und reiste für forum in die Ukraine

Als partizipative Debattenzeitschrift und Diskussionsplattform, treten wir für den freien Zugang zu unseren Veröffentlichungen ein, sind jedoch als Verein ohne Gewinnzweck (ASBL) auf Unterstützung angewiesen.

Sie können uns auf direktem Wege eine kleine Spende über folgenden Code zukommen lassen, für größere Unterstützung, schauen Sie doch gerne in der passenden Rubrik vorbei. Wir freuen uns über Ihre Spende!