- Kultur

Instagrammable

On the temporary exhibition Best of Posters

There are widely differing views on what should be shown in a museum – both in Luxembourg and abroad. This is why we have such a diverse and enriching museum landscape, from the rural history museum to the contemporary art gallery. It also raises the question of the role of museums in our society, i.e. from sharing knowledge to offering inclusive spaces for critical dialogue. Despite difficult discussions in recent years, ICOM presented its new definition in 2022, which defines quite clearly (and at the same time vaguely) what a museum is or should be: “A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.”1 This review will take a closer look at the temporary exhibition Best of Posters at the Lëtzebuerg City Museum and reflect on where to situate it within this definition.

The show explores the history of posters. The title is both catchy and clumsy (spoiler alert!): Best of Posters. 100 posters from our collections, selected by the public.2 First of all, ICOM clearly states that a museum is defined by what’s in it, not by how it presents its holdings (although the two often go hand in hand), so we won’t focus on Anouk Schiltz’s neat exhibition design.

The show opens with a brief introduction to 500 years of poster history, ending with a recent piece by artist Eric Mangen (2022) – an odd twist in the chronological narrative. The fact that poster art is often deconstructed by contemporary artists nowadays may be true, but it is hardly relevant here. It is simply not part of the ongoing evolution of posters per se.

Participatory practices

This section is followed by a description of the participatory concept on which the exhibition is based. We’ve known for a long time that cultural institutions in Luxembourg have to adapt to a constantly changing audience. This was for instance described by Marie-Paule Jungblut in issue 354 of forum back in 2015.3 Transformation processes in museums are a matter of learning by doing, ideally backed up with thorough methodological considerations. This leads me to my first point: just because a project calls itself “participatory” doesn’t necessarily mean it involved the participants in a meaningful way. In the case of Best of Posters, the attentive reader of the exhibition texts is bound to notice this.

The exhibits were selected by six small “expert groups”; museum security guards, Creamisu (a sociocultural space for homeless people), a school class, museum guides, five graphic designers and a few members of the Amis des Musées. A thoroughly laudable approach to shed the elitist reputation of the museum world. As exciting and promising as the selection of the groups is, the approach is methodologically problematic. The only tangible result of this participatory collaboration in the exhibition itself is that the 100 most liked (“best-rated”) posters from a selection of 254 thematically sorted posters are on show. In terms of content, the collaboration did not have any significant bearing on the exhibition, apart from a few quotes taken out of context (i. e. “Almost all of them are great posters”, visitor; “Bombs, cannons and a naked woman!”, museum guide). The 14 themes according to which the posters were sorted and which the “juries” voted on are not included in the exhibition. Yet important questions could have been raised: How does a graphic designer explain the design of a lottery poster from the postwar era? How do the children interpret it? How relevant do disadvantaged social groups find a poster about capitalist society? The list goes on and on.

If any relevant content at all emerged from the cooperation with these “expert groups”, it was not included in the exhibition. Also, the question of the added value for museum visitors should be raised. What will visitors take away from an exhibition of 100 posters that a few people liked best? Since any content developed during the participatory process is missing, there is little added value for museum visitors.

Let’s discuss the exhibition rooms where the 100 best posters are shown. Visitors can navigate the rooms using QR codes, also available online at http://xbtn.site. It’s unclear whether the rooms are ordered by overarching themes, though attentive visitors may be able to guess them from the posters on display.

There are some interesting descriptions of posters, but most of the content is largely irrelevant in terms of the theme of the exhibition.

There are some interesting descriptions of posters, but most of the content is largely irrelevant in terms of the theme of the exhibition. To name a few examples, a poster that was obviously intended to advertise an international exhibition of gastronomy and culinary art for industry and commerce from 1912 is rather unimaginatively described as a “Poster for the International Exhibition in Luxembourg”. Yet the poster boasts a wonderful motif that should be contextualised or at the very least explained to the visitor. Elsewhere, the exhibition makers Anne Hoffmann, Guy Thewes and Kyra Thielen choose to feature a biography about Auguste Trémont without going into the design of a poster of his on display. The same applies to a poster of the Schueberfouer, where the visitor is given a long introduction to the history of the funfair without any mention of the visual content of the poster.

Missing information and mistranslation

All in all, the short descriptions of the posters are all too often literal translations of the text featured in the posters and, thus, hardly contribute to explaining them. A poster for a beer festival in Clausen reads “Festival de la bière”. The description reads: “Poster for the Beer Festival”. The beer festival! This is a poster with a well thought-out design by Pe’l Schlechter, but again the motif is not even mentioned. Also, don’t not miss the “Poster for the Great International Women’s Gymnastics Festival”. The great festival! Or the imaginatively titled “Poster advertising gymnastics”.

If you read the texts carefully, you’ll notice a lot of content-related and translation errors. For example, only in the first two rooms of this part of the exhibition:

The “Poster for the car race Circuit international”, 1900-1940, actually dates back to 1906;

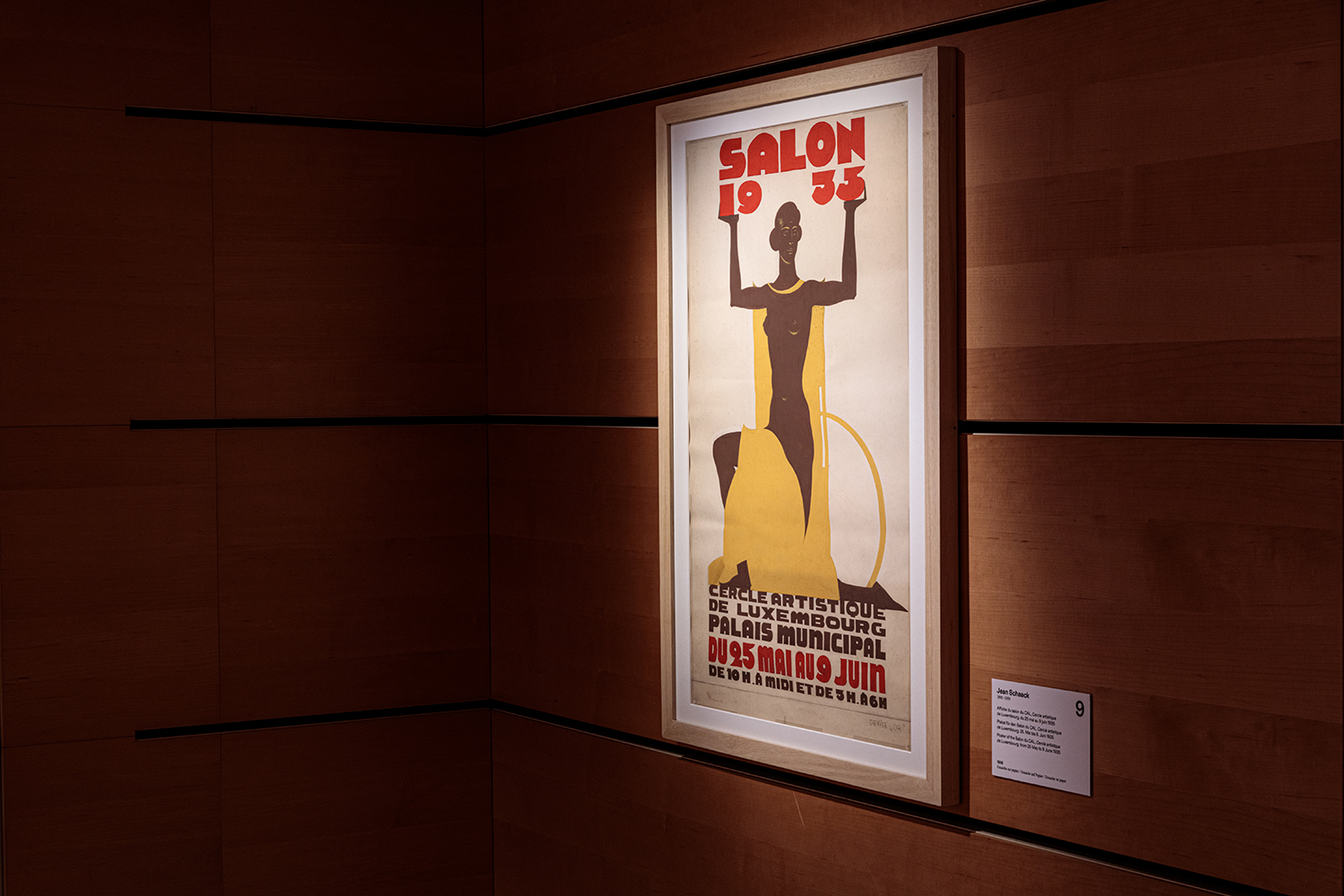

Jean Schaack’s poster for the “Salon du CAL” of 1935 is in fact not the poster, but the project that the artist submitted for the competition;

“Feller Frères” mentioned on the gymnastics poster from 1933 isn’t the artist, but the print office. The artist’s signature, though, is on the poster;

The print office of the poster “Poster advertising gymnastics, circa 1950” (Kremer-Muller) only opened in 1958;

The “Plakat für das Theaterstück ‘Wir gehen auf den Bock’ ein Burgspiel von Alain Atten” is incorrectly translated as “Affiche pour la pièce de théâtre ‘Nous allons au Bock’, une pièce de château fort de Alain Atten’;

A poster for the Socialist Party by Robert Lentz is dated “1950–1980”, although Lentz died in 1970;

Almost none of Pe’l Schlechter’s posters are accurately dated, with time spans of up to thirty years, although the artist could have been consulted.

Design vs. purpose

In an exhibition about posters, visitors expect content about the design of the posters on display (what do we see and why?), not just a mention of the featured theme and biographical information about the artist. Now, of course, you could say that the exhibition is based on a participatory concept. You can’t have everything, right?

Coming out of the exhibition, it remains unclear what the underlying theme is. The description of the show states that “it illustrates the development of Luxembourg and international graphic design during the 20th century.” The exhibition is certainly beautifully designed, though you wonder why only a fraction of the original posters are on display when it’s supposed to be illustrating the history of these objects. Possibly there are good reasons for this, but they are not explained to the visitor.

Conclusion

To conclude: the show doesn’t really do what it says on the tin, billed in the opening as an exploration of 200 years of poster history. An intriguing animation by the artist Daniel Wangen is the highlight of the exhibition, as it invites visitors to actually engage with the content of the posters. The exhibition itself is very instagrammable and invites you to wander through the rooms without having to think too much. It’s worth pointing out that the ICOM definition of museums questions this approach to exhibition-making.

The museum also features two other exhibitions: a permanent exhibition4 and a temporary exhibition about the history of associations in the capital. At first glance, the latter sounds far less exciting than fancy posters. But here the visitor is actually offered a “best of”, namely the highlights of 200 years of associative life in Luxembourg. This exhibition shows that the Lëtzebuerg City Museum is capable of offering content as well as context, inviting visitors to reflect on today’s society. But this was obviously not the case in the exhibition discussed here, “best of” branding notwithstanding.

In Luxembourg, there is rarely a debate about the relevance of a museum exhibition and critical discussions about the actual content are few and far between. Just as publications are critically reviewed in scientific journals, the same should apply to Luxembourg’s well-funded museum sector, as this exhibition review hopefully demonstrates.

1 ICOM Museum Definition, 24 August 2022, URL: https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition (checked on February 21, 2023).

2 Anne Hoffmann, “Best of Posters. 100 Plakate aus unseren Sammlungen, vom Publikum ausgewählt”, in: Ons Stad, 2022, 126, p. 54-55.

3 Marie-Paule Jungblut, “Museum as a social hub ? Historische Museen im Angesicht einer sich verändernden Bevölkerungsstruktur”, in: forum 354 (September 2015), p. 41-45, 42.

4 Michel Pauly, “Lëtzebuerg City Museum 3.0”, in: forum 374 (Juni 2017), p. 58-60.

Henri Wilmes first studied history, then economics. He has lived and worked in the United Kingdom for many years as an economic consultant.

The exhibition Best of Posters will be on display at the Lëtzebuerg City Museum until January 14, 2024.

Als partizipative Debattenzeitschrift und Diskussionsplattform, treten wir für den freien Zugang zu unseren Veröffentlichungen ein, sind jedoch als Verein ohne Gewinnzweck (ASBL) auf Unterstützung angewiesen.

Sie können uns auf direktem Wege eine kleine Spende über folgenden Code zukommen lassen, für größere Unterstützung, schauen Sie doch gerne in der passenden Rubrik vorbei. Wir freuen uns über Ihre Spende!