- Reichtum

Richer and happier?

Why people in Luxembourg are not as happy as they could be and what we can do about it

In March 2024, STATEC released the PIBien-être report on how life is in Luxembourg. The report included a figure showing the relationship between a country’s wealth, measured by its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, and the average life satisfaction of its residents. Luxembourg stands out as the richest country with an average GDP per capita of 100.000 €. However, it is not the country where people are most satisfied with their lives, ranking 8th in life satisfaction, just after the Netherlands and Poland. Notably, these two countries have GDPs per capita that are 50 % and 10 % of Luxembourg’s, respectively.

Shouldn’t people in richer countries be happier? What is the purpose of pursuing economic growth if it does not improve lives? The short answer is that GDP and its growth are not the only factors that matter for well-being. Other factors, such as health, social relations, meaningful work and freedom, are also crucial. Focusing solely on GDP can lead to neglecting these important aspects of people’s lives.

GDP growth has the potential to make lives more comfortable, richer, healthier, enjoyable and environmentally sustainable. In many countries, however, the potential negative consequences of economic growth (inequality, unhealthy lifestyles, loss of social cohesion, pollution, loss of biodiversity and environmental degradation) can offset its benefits with negative net effects on well-being. If we care about delivering socially and environmentally sustainable lives that are worth living, then how we promote and achieve growth matters.

Economic growth can be compatible with well-being in countries that promote full employment, social safety nets, protect social capital, and reduce income inequalities. These countries might experience slower economic growth, but slow growth is not necessarily a bad sign. It may indicate a system better organized to support quality of life. Conversely, if economic growth leads to isolation, stress, inequality, and environmental degradation, then well-being may decline.

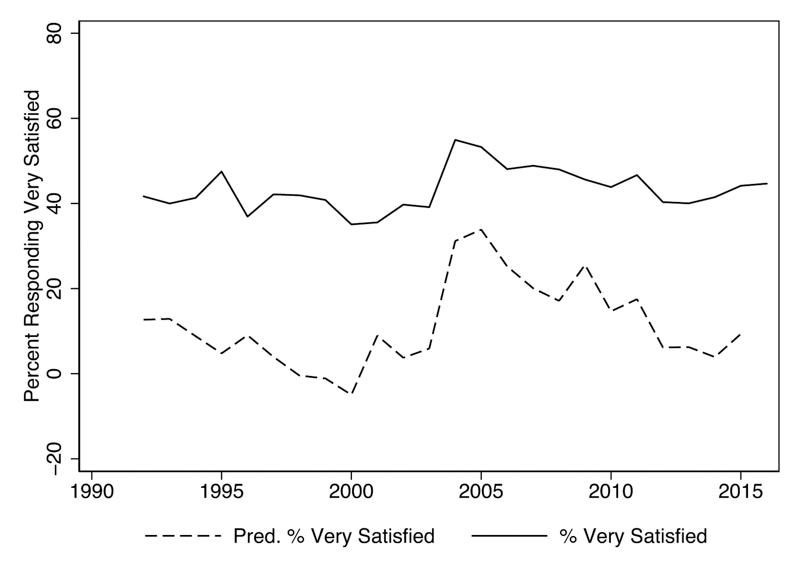

An analysis of long-term changes in well-being in Luxembourg revealed that life satisfaction has not significantly changed since the 1980s due to contrasting forces that offset each other. While life satisfaction should have increased due to rising social capital (generalized trust increased from 25 % in 1986 to 38.5 % in 2022 after peaking at 43.3 % in 2016) and stable social expenditures, it was limited by increasing income inequality (+6 points on the Gini index) and higher unemployment (from an average of 2.3 % between 1980-2000 to about 5.4 % from 2000 onwards). The comparison of observed life satisfaction with predictions from an econometric model based on these socio-economic changes can help illustrate this point. Figure 1 shows that short-run changes and long-run trends of predicted life satisfaction match the observed data well, suggesting that the model has high predictive power.

The well-being prevalent in a nation depends on the relative strength of each force; if they are equal, well-being does not change. This can explain why, despite being the richest European country, Luxembourg is not necessarily the one where people are most satisfied.

Research demonstrates that individuals with more vibrant social lives tend to be happier and are more likely to embrace pro-environmental behaviors. They also place less importance on social comparisons, which fuels consumption […].

Since the 1960s, positive psychologists and other social scientists have proposed various solutions to measure well-being. Life satisfaction emerged as a reliable and valid measure of self-reported well-being, and it is currently widely used in social sciences, including in economics. It reflects what individuals deem relevant to their quality of life, including both economic and non-economic concerns. The introduction of life satisfaction measures has revolutionized research by allowing us to ask how much modern societies benefit from economic growth. Surprisingly, the prevalent answer is: very little. 1

Two main theories have been suggested to explain this result: adaptation and social comparisons. Both suggest that income aspirations hamper subjective well-being. Aspirations may depend on one’s past income (adaptation) or on the income of one’s reference group (social comparisons). In the first case, the negative effect of higher income depends on people’s past achievements. On the basis of what they get, people set their future aspirations. For example, last year’s wage is the reference point for the current year’s wage: if the actual wage does not meet the aspirations, the result for well-being is negative. The second mechanism works in a similar way but relies on comparing people’s achievements with those of others. In this case, the effect of higher income for well-being depends on a relative amount: do I earn more, the same, or less than my colleagues, neighbors and friends? These “others” may comprise various groups of people whom we consider a reference point to assess our success. To the extent that the benefits of income growth are relative (i.e., deriving from comparison with others), then whenever one person gains, another loses, and societal well-being remains unchanged. These two theories are compatible with a third one, defensive growth, which adds the possibility that the economy may grow as result of the damages it creates.

in Luxembourg. Source: Sarracino and O’Connor, 2021

Defensive growth theory describes economic growth as a double-edged sword. The classical representation of economic growth suggests, it is always beneficial, like a growing pie from which everyone gets larger and larger slices. In contrast, defensive growth theory describes a growth that occurs in a vicious cycle, growing from poisoning the cake itself: economic bads (negative externalities) contribute to economic growth and additional growth contributes to yet more negative externalities2. For example, work environments characterized by distrust can be extremely difficult, time-consuming and nerve-wracking. To compensate, companies pour considerable resources into observing and incentivizing employees, as well as programs to cultivate a positive social environment. Think of the many solutions available on the market to control employees’ work activity or the legal expenses to write sophisticated contracts to prevent or discourage free riding and moral hazard. If families don’t have sufficient time to care for their children or elderly parents, they can hire caregivers; if people are lonely, their friends are too far away or the city is too dangerous to be out at night, they can purchase home entertainment systems; if people like to sing, they can rent an individual karaoke booth to sing to themselves. This applies to environmental negative externalities too. For instance, if drinking water is polluted, people can install filters to purify it.

Defensive growth theory assumes that money offers a defense – real or illusory – against the erosion of non-market resources, such as social connections and a pristine natural environment. The tragedy is that the sum of the individual solutions ends up worsening the living conditions of all: individuals’ attempts to compensate or defend their well-being, expand the demand for goods and services, thus fueling consumption and further expanding market activity. In sum, economic growth can result from the substitution of non-market sources of well-being with market goods and services.

When growth is defensive, money becomes an insurance against the uncertainty of the future: when trust declines, cooperation to solve collective problems declines too, and people will consider private solutions as the only hope to protect themselves and their loved ones. From this point of view, economic growth loses its appeal as a measure of progress.

Is there a way to break the vicious cycle and move societies towards high well-being lives that are compatible with social and environmental sustainability? Decades of well-being studies reveal a promising path forward – one that can initiate a positive cycle where prioritizing well-being, through policies that foster social capital, reduces individuals’ dependency on consumption and encourages collective action. This approach favors stronger social connections and protects the environment. Research demonstrates that individuals with more vibrant social lives tend to be happier and are more likely to embrace pro-environmental behaviors. They also place less importance on social comparisons, which fuels consumption, and exhibit greater willingness to collaborate with others in addressing shared challenges.

Moreover, investing in well-being yields productivity gains that can be harnessed to reduce working hours without compromising economic output. Estimates indicate that increasing life satisfaction by one unit in countries like France or Germany could result in productivity gains equivalent to nearly 80 working hours per year.3 This means we could collectively work two weeks less annually without sacrificing the output. Further studies indicate that one unit increase in job satisfaction is associated to 5 % higher labor productivity and nearly 6 % increase in the growth rate of labor productivity.4 These gains could be used to shorten the workweek, enable earlier retirement or finance policies aimed at enhancing well-being and strengthening social connections, all while maintaining economic output unchanged. A policy agenda that promotes social safety nets, protects social capital and employment and reduces income inequality would benefit individuals in rich and poor countries, and contribute to a socially and environmentally sustainable economy. An economy that is not driven by defensive needs but by creativity; an economy that grows less according to traditional standards, but one that is better suited to support people’s quality of life. Let’s transition from the vicious to the virtuous cycle.

Francesco Sarracino is head of the research unit on well-being and entrepreneurship at STATEC. His work aims at identifying policies to make economic growth compatible with people’s well-being and to pursue socially and environmentally sustainable development. He holds a PhD in development economics from the University of Firenze (Italy).

Kelsey J. O’Connor is a Researcher in the Economics of Well-being at STATEC Research. His research focuses on assessing both the causes and consequences of subjective well-being (or happiness), with the goal of contributing to a redefinition of progress in national discourse. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Southern California.

1 Richard A. Easterlin & Kelsey J. O’Connor, “The Easterlin paradox”. In: Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 1-25.

2 Stefano Bartolini & Luigi Bonatti, “Endogenous growth, decline in social capital and expansion of market activities”. In: Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 67(3-4), 2008, p. 917-926.

3 Charles H. DiMaria, Chiara Peroni & Francesco Sarracino, “Happiness matters: Productivity gains from subjective well-being”. In: Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(1), 2020, p. 139-160.

4 Chiara Peroni, Maxime Pettinger & Francesco Sarracino, “Productivity Gains from Worker Well-Being in Europe”. In: International Productivity Monitor, 43, 2022, p. 41-61.

Als partizipative Debattenzeitschrift und Diskussionsplattform, treten wir für den freien Zugang zu unseren Veröffentlichungen ein, sind jedoch als Verein ohne Gewinnzweck (ASBL) auf Unterstützung angewiesen.

Sie können uns auf direktem Wege eine kleine Spende über folgenden Code zukommen lassen, für größere Unterstützung, schauen Sie doch gerne in der passenden Rubrik vorbei. Wir freuen uns über Ihre Spende!